By Pablo Gamba

Originally published in Spanish at Los Experimentos blog.

Translated by Venezuelanvoices.org

Image: Cuando quiero llorar no lloro

The premiere of Cuando quiero llorar no lloro (When I Want to Cry, I Don’t Cry) in 1973 marked the beginning of a national cinema that was, for the first time, capable of regularly attracting significant numbers of viewers in Venezuela. Alfonso Molina (1997) argues that the film directed by Mexican Mauricio Walerstein, based on the novel of the same name by Miguel Otero Silva (1970), was “the first major encounter between Venezuelan cinema and its natural audience” (p. 76). It ranked second in box office revenue that year (González, Pino, and Vilda, 1976).

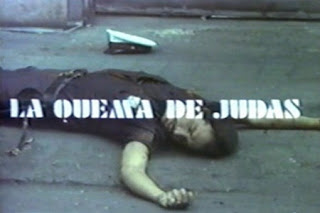

This was followed by the release of La quema de Judas (The Burning of Judas), directed by Román Chalbaud, which ranked fourth among the highest-grossing films in 1974, while Crónica de un subversivo latinoamericano (Chronicle of a Latin American Subversive), by Walerstein, who settled in the country, reached seventh place in the first half of 1975. In 1976 and 1977, three national films were among the ten highest-grossing films in Caracas and its metropolitan area (Film Industry Statistics, n.d.).

These box office successes were followed by the granting of the first state credits to finance the production of commercially released feature films in 1975 and 1976. This decision was made in the context of the unprecedented rise in oil prices, the country’s main source of income, which occurred in 1973 due to the conflict in the Middle East.

However, the data alone does not explain why Molina called the premiere of Cuando quiero llorar no lloro (When I Want to Cry, I Don’t Cry) the “starting point” of national cinema (p. 76). Nor do the box office figures suffice to explain why the government decided to promote this cinema with loans.

These are the questions I will attempt to answer in this essay, in which I will defend the thesis that what happened in the period beginning in 1973 was the legitimization of national cinema. Following Pierre Bourdieu, this means that for the first time it received recognition from one or more authorities with the necessary power to legitimize it, although this does not in itself clarify which authorities these were. Asking these questions is important in order to clarify the Venezuelan nature of this national cinema. Each society can legitimize its cinema in different ways, according to its uniqueness and the moments in which it gives this recognition.

The filmmakers’ strategy

The strategy with which filmmakers achieved the legitimization of the new Venezuelan cinema had a commercial aspect and a political-cultural aspect. I should clarify that I also use “strategy” in the sense that it has in Bourdieu’s theory of social fields. I must therefore emphasize that it can go beyond the conscious or explicit intentions of the agents. Strategies are shaped according to “socially constituted dispositions” (Bourdieu, 1971 [2002], p. 107) or habitus, and the objective relationships that exist in a particular field and one that encompasses them all, despite their relative autonomy: the field of power. To achieve legitimacy or recognition, one must surrender to the game played in these spaces and follow its rules.

Returning to the New Venezuelan Cinema, its makers were directors of films in whose independent production they also participated. This differentiated them from the national co-producers of foreign films and from the productions of Venezuelan film service companies or distributors. It also differentiated them from those who made films at universities.

To describe their commercial strategy, I take as a reference Cuando quiero llorar no lloro, which became a model followed by other Venezuelan films of the time in their quest for box office success. The formula consisted, on the one hand, of adapting the country’s political and social issues to the treatment given to similar issues in foreign films that were box office hits in Venezuela. For the same goal, there was also a quest to conform, as far as possible, to the films that were taken as international models in terms of style and production values. These are the “industrial characteristics” that Alfonso Molina (1997) attributes to the films of the new Venezuelan cinema (p. 76).

Although Cuando quiero llorar no lloro tried to resemble foreign cinema through the use of color film, Panavision equipment, slow motion, and special effects, improving technical aspects was important for this attempt at standardization. The hiring of personnel with international experience for the photography, editing, and sound of some films, starting when state credits began to be awarded, is revealing of this quest.

Independent films also turned to a group of national actors whom producers believed had the ability to attract audiences, as indicated by their participation in the leading roles of several films. Among the most prominent were Miguel Ángel Landa, Orlando Urdaneta, and Asdrúbal Meléndez, and among the actresses, Hilda Vera. Part of the formula for their success was also to make them recognizable as film actors, with producers following the trend of the time: to pit films against television.

As for the foreign models of the New Venezuelan Cinema, the first was what Ambretta Marrosu (1979) calls “spectacular European political cinema” (p. 29), whose emblematic figure is Costa-Gavras. The story of the guerrilla fighter who dies at the hands of his torturers after a failed mission, one of three stories told in Cuando quiero llorar no lloro, points in this direction, although its source is in national literature. This can be seen both in the political theme and in the formal playfulness of the editing, characteristic of the French-Greek filmmaker’s style, in which classical narrative clarity dominates with touches of subtle modernism.

This is even more evident in Crónica de un subversivo latinoamericano, which recounts the kidnapping of a US military attaché by guerrillas in 1964 and was released three years after Costa-Gavras’ State of Siege (France-Chile, 1972), based on a similar case in Uruguay. The chronological order of events in the fiction is also subtly played with in the editing of this Venezuelan film, whose fake interviews can be referenced in another figure of spectacular European political cinema, the Italian Francesco Rosi.

La quema de Judas (1974), Chalbaud’s first New Venezuelan Cinema film, also seems to follow Costa-Gavras, in the film adaptation of the investigator character from his play of the same name. La compañía perdona un momento de locura (The company forgives a moment of madness, 1978), Walerstein’s third film in Venezuela, is based on the Venezuelan play of the same title by Rodolfo Santana, which can also be found referenced in spectacular political cinema: La classe operaia va in paradiso (The Working Class Goes to Heaven,Italy, 1971), by Elio Petri.

Films about the guerrilla movement make up what could be identified as the first cycle of New Venezuelan Cinema, and the dynamics of the formula are evident in the significant variations that existed in other films within the unity provided by the political theme. One consisted of relating the protagonist’s past in the rural guerrilla movement to his situation in the city, in the historical present of 1970s Venezuela, as in Sagrado y obsceno (Sacred and obscene, Román Chalbaud, 1975) and Compañero Augusto (Comrade Augusto, Enver Cordido, 1976). Another was to go back to the Federal War of the 19th century to give a familiar, national, and local historical context to the formation of the guerrilla fighter, as in País portátil (Portable Country, Iván Feo and Antonio Llerandi, 1979). La quema de Judas took an early turn on the subject by shifting the focus from the guerrillas to the police, whose corruption is a synecdoche for the rottenness of the regime against which some took up arms.

But the guerrilla cycle ran its course in three years. The character’s return in País portátil was part of a different cycle of historical films, which began with Fiebre (Fever, Juan Santana, 1976) and continued at a rate of one release per year with Se llamaba SN (It was called SN, Luis Correa, 1977) and El Cabito (The Little Sargeant, Daniel Oropeza, 1978). This also demonstrates the ability of the New Venezuelan Cinema to renew itself in order to maintain its success.

In 1976, there was a more significant change in the formula with Soy un delincuente (I Am a Criminal). Clemente de la Cerda’s film had a precedent in another of the parallel stories in Cuando quiero llorar no lloro, that of the criminal who escapes from prison. However, not only does it not follow the model of spectacular European political cinema in terms of style, but it even clashes with the norms that define what is considered professional in cinema. It expresses what the filmmaker and Alfonso Molina agreed to call “balurdo aesthetics” (Molina, 1997, p. 77), which means “poor quality” or “unpleasant,” according to the Dictionary of Americanisms.

However, Soy un delincuente also replicates the “industrial aspirations” of the New Venezuelan Cinema. Despite the dissidence of its style, it makes the protagonist a spectacular antihero like those of Hollywood, albeit without a tragic fate, in a way that crystallized a myth of the “malandro” that has endured in Venezuelan cinema. The search for the spectacular is also evident in the character’s debauchery in the pleasures of sex, alcohol, and drugs. This, combined with his status as a delinquent spokesperson for a discourse that justified his conflict with police repression, had an appeal never before seen in commercial national cinema because of its challenge to moral and political censorship.

With more than 450,000 viewers, Soy un delincuente was the highest-grossing film of the New Venezuelan Cinema (Obras cinematográficas estrenadas, n.d.), which in the year of its release consolidated its position in the market with five films, three of which made it into the top ten list of highest-grossing films (Estadísticas de la industria cinematográfica, n.d.).

Another significant shift in the formula with which the new Venezuelan cinema initially sought to attract audiences was in its foreign sources. Such is the shift toward classic Mexican melodrama in Chalbaud’s films. The reference is recognizable in Sagrado y obsceno, but it becomes more relevant in El pez que fuma (1977), which is a self-parody with a background of political criticism, like the cabaret films that proliferated in Mexico during the corrupt government of Miguel Alemán. This links it to the rise of the other major cycle of New Venezuelan Cinema, along with those of the guerrilla and history: that of comedies. It began in 1976 with Los muertos sí salen (The Dead Do Come Out) by Alfredo Lugo, and in the same year as El pez que fuma, Los tracaleros (The Hustlers) by Lugo and Se solicita muchacha de buena presencia y motorizado con moto propia (Girl with Good Looks and Driver with his Own Motorcycle Wanted) by Alfredo Anzola were released.

With the rise of comedy, the political and social concerns that had originally characterized New Venezuelan Cinema began to fade. The most illustrative example is Chalbaud, when in Carmen la que contaba 16 años (Carmen, who was 16 years old, 1978) he turned to the leading couple of a soap opera of the moment to make a Venezuelan parody of Prosper Merimée’s melodrama. Something similar can be said of Enver Cordido in his second feature film, the underrated comedy Solón (1979). Soy un delincuente had a sequel, Reincidente (Repeat Offender, 1977), which differed from the first because it was not an independent film, but rather a co-production by leading film distribution and service companies in the country, with another actor in the lead role and American action cinema as its model. In 1978, a national film was released that was paradigmatic for its confrontation with the New Venezuelan Cinema: Simplicio, by internationally renowned fashion photographer Franco Rubartelli, a story about a boy and his grandfather aimed at family audiences.

A diversity of audiences

Having said this about the formula with which the New Venezuelan Cinema sought box office success, its dynamics, and the diversity to which it led, it is necessary to move on to the problematic task of speculating about why the national audience made these films box office hits.

The first thing to do, in this regard, is to question Molina’s (1997) hypothesis, according to which Cuando quiero llorar no lloro “established a relationship of identity between the viewer and what was happening on the screen. A way of speaking, of acting, and, ultimately, a way of being Venezuelan. For the first time, the national audience saw a story, a dramatic process, and characters that belonged to them” (p. 76). Identification could also have occurred on the basis of the adaptation of foreign cinema that was taken as a model, and the “way of speaking, acting, and […] being Venezuelan” could have been referenced by other popular audiovisual representations: those of national radio and television.

In Jesús María Aguirre (1980), there is another explanation based on audience segmentation. He argues that support for the New National Cinema did not come from viewers who recognized it as their own because it was Venezuelan, but because of the common experience of a particular group, those who had participated “really or empathically in the youth upheavals of the last decade [the 1970s]: the declining guerrilla adventure, hippiedom, youth power, etc.” (p. 10).

One problem is that Aguirre does not attempt to demonstrate this as can be done, for example, by identifying textual elements that indicate that the stories told cannot be properly understood without reference to the context of this generational experience. But he comes close to the truth when he identifies these viewers as rebels in a countercultural sense.

In the New Venezuelan Cinema, there was a stance that was dissident in culture. It became openly confrontational in Soy un delincuente, in terms of aesthetics, morality, and politics, but more significantly, it was expressed in the selection of national literary works that the films adapted with reference to the cultural context of the time. These were not the Venezuelan classics that television enshrined as official mass audiovisual culture by turning them into soap operas or miniseries. They were works by authors such as Adriano González León, who had been part of one of the “cultural left” groups (Chacón, 1970) during the guerrilla era, or Miguel Otero Silva, who had renounced the communist militancy of his youth but maintained an “independent leftist position” (Pacheco, 1994, p. 186).

Chalbaud could also be considered part of the “cultural left,” and his play Sagrado y obsceno was censored in 1961 for political reasons. Canción mansa para un pueblo bravo (Gentle Song for a Brave People, 1976), by Giancarlo Carrer, references Alí Primera, an iconic singer-songwriter of that political movement in the country, in its title and soundtrack. As for the testimonial novels adapted in Soy un delincuente and Crónica de un subversivo latinoamericano—the eponymous work by Gustavo Santander (1974) and FALN, Brigada Uno (FALN, Brigade One, 1973), by Luis Correa, respectively—the protagonist of one expresses sympathy for Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, while the author of the other was the guerrilla commander of the unit responsible for the kidnapping it recounts.

This positioning of cinema in a culturally dissident and left-wing space leads us to consider aspects of the experience that Aguirre does not take into account and that do not refer to the past youth but to the early maturity of that same generation in the present, in the so-called “Saudi Venezuela.” In the country of the oil boom, opportunities opened up for many young adults, including the rebels who had wanted to change society, to embark, like the protagonist of Compañero Augusto, on the search for easy and quick wealth. But this clashed with another form of violence, social violence, that of the democracy against which the guerrillas had fought: the misery of Soy un delincuente, accompanied by political police violence.

This was a moral and political dilemma that the New Venezuelan Cinema posed, particularly to its young adult audience. In this context, we must also consider films that end with the characters continuing to fight even after they know they have been defeated (Crónica de un subversivo latinoamericano and País portátil) or try to see their commitment to their dead comrades through to the end, even if it means a futile revenge in which justice and vengeance become confused (Sagrado y obsceno).

Other films, on the other hand, focused on different problems and new areas of struggle that were opening up in democracy, such as Se solicita muchacha de buena presencia y motorizado con moto propia and La empresa perdona un momento de locura or Manuel (Alfredo Anzola, 1980). In all these ways, the films of the New Venezuelan Cinema appealed to a generation, even if they did so without questioning their contradictory spectacularity or their aspiration to conform to the foreign products with which they competed in the market.

However, it is doubtful that the young adults identified by Aguirre were the core audience for all the films. El pez que fuma, for example, is not aimed at viewers of Costa-Gavras or Soy un delincuente, but rather at those with tastes shaped by Mexican melodrama. Similarly, it appeals to the complicity of those familiar with the repertoire of Latin American popular music classics featured in the soundtrack (Paranaguá, 1993, p. 59). But this film is also emblematic in terms of its criticism of “Saudi Venezuela,” which can be seen reflected in the brothel, “where everything is bought and sold, especially power” (Molina, 2001, p. 75). The parodic appropriation of its film sources should also be considered an expression of cultural resistance by a Latin Americanist left.

Nor do the viewers of Los muertos sí salen or Luis Armando Roche’s El cine soy yo (I am Cinema) seem to fit the profile outlined by Aguirre. The former uses well-known television comedians, but with a style that is perhaps closest in the New Venezuelan Cinema to the cinema of poetry proposed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Roche’s film starred Juliet Berto, which referenced, for example, Jean-Luc Godard and Glauber Rocha’s Claro (Italy, 1975). Lugo and Roche also appropriated genres in a way that requires the complicity of a cinephile audience: the horror comedy in Los muertos sí salen, the caper movie in Los tracaleros (1977), and the European version of the road movie in El cine soy yo. Therefore, it must be assumed that these films were aimed at national audiences of so-called “art cinema.”

However, the dead referred to in the title of Lugo’s first film refer to the regime of Marcos Pérez Jiménez and the US-backed military dictatorships, while the three protagonists are forced to take up arms, putting them in a position analogous to that of guerrillas. In El cine soy yo, Roche pays tribute to the mobile cinemas of the Cuban Revolution and also to the film clubs that identified politically with the Left (Anzola, Fernández, and Messina, 1995) and were persecuted by the government and pro-government gangs.

Other audiences sought by the New Venezuelan Cinema were young workers from working-class backgrounds, as evidenced by the cast of characters in Se busca muchacha de buena presencia y motorizado con moto propia. Chalbaud made the rebellious high school students of the present the protagonists of El rebaño de los ángeles (The Flock of Angels, 1979), which could appeal both to teenagers like themselves and to viewers old enough to be their parents. It also targeted women: the film stands out in New Venezuelan Cinema for its female protagonist, who is surrounded by other women characters, including teachers and students at a high school. These are not the prostitutes of Mexican cinema in El pez que fuma.

In Manuel, the woman is a co-protagonist and is involved in a community’s struggle to defend its fishing grounds from real estate developers. She also challenges religious morality because she has a carnal love affair with a priest, as well as the conventions of melodrama and bourgeois morality, because of the love and friendship triangle formed by the main characters.

In short, each cycle, and some of the individual films, attracted different audiences. The sum of all these viewers would have been the audience for the New Venezuelan Cinema. Its most comprehensive characteristic would be cultural and political identification with the Left, understood in all the breadth that its expressions have had and continue to have in Venezuela, as in other countries.

The audience, however, could not legitimize the New Venezuelan Cinema on its own, even in 1976, at the height of its success. Selling many tickets is not a sufficient condition, nor even a necessary one, for the consecration of a filmmaker, as demonstrated by the prestige of filmmakers whose films are not box office hits. It is festivals, awards, critics, and film clubs or similar institutions that are capable of giving them a prestige similar to that of writers or painters whose success they recognize and which artists pursue (Rivas Morente, 2012). This can give certain films a legitimacy similar to that of works of art, insofar as they are distinguished, as “auteur cinema” or “art cinema,” from “entertainment.”

We must now turn to the political and cultural aspects of the strategy behind the New Venezuelan Cinema to see if there we can find the answer to the question of how this cinema was able to legitimize itself, before which authorities this occurred, and how its success with audiences influenced it, if indeed it had any impact.

The political-cultural aspect

The first thing to note in relation to the political-cultural aspect of the strategy is the “extraordinary resistance” that Alfredo Roffé (1997a) believes exists in the country’s media towards “any critical activity related to cultural industries.” Criticism is “perhaps the weakest of the film institutions” (p. 60).

To this we must add that in Venezuela there were no major festivals or awards when the New Venezuelan Cinema began. The most important one organized later, in the 1970s, was dedicated to another type of cinema, the experimental films shot in the home format of Super 8.

In the absence of this institution, there were international festivals to which some films had access. Cuando quiero llorar no lloro and La quema de Judas were selected for the Moscow Film Festival, and El pez que fuma won the award for best film at the Cartagena Film Festival, for example. But this seems to have led to nothing more than another characteristic that equated these films with foreign cinema in the eyes of the national audience, added to the participation of prestigious actors on the international festival circuit, such as Juliet Berto and the Mexican Claudio Brook, who worked on Simón del desierto (Simón of the desert, 1965) and other films by Luis Buñuel, as well as La quema de Judas and Crónica de un subversivo latinoamericano.

The film that best demonstrates the irrelevance of international awards in the country is Soy un delincuente, which received a jury mention at the Locarno Festival. In Venezuela, it was and still is undervalued, as evidenced by the aforementioned description of “balurdo aesthetics.”

The weakness of criticism and the lack of relevant awards highlight the relevance of investigating how this particular society legitimized its cinema, as indicated at the beginning. These are facts that cast doubt on whether it could have been analogous to the arts implicit in the notions of “auteur cinema” and “art cinema,” which are often treated as if they had universal validity. The situation described even calls into question the existence of an autonomous film industry in Venezuela, given the absence of authorities with recognized legitimate power to legitimize and give artistic value to films, and to establish their directors as auteurs.

Another characteristic of Venezuelan criticism is that since the 1960s, its most influential figures have been linked to universities (Colmenares, 2014). This placed it in a field in which dissident leftist thought exerted a decisive influence. After the defeat of the armed struggle, conflicts with the regime continued in the universities, where only in 1973 was the hegemony of the two-party system established. One example is the Renovación Universitaria (University Renewal) movement of 1969, one of the “youth uprisings” in which the future viewers of the New Venezuelan Cinema participated “concretely or empathically,” according to Aguirre.

It was critics linked to the academic field and filmmakers who also worked in universities who formulated the explicit political-cultural aspect of the national cinema strategy. Their banner was the Cinema Law, whose approval was defended by appealing to values such as the social and cultural importance of national cinema in the face of state powers. It was, therefore, a strategy that was not deployed in the dubious field of cinema but in the field of power. The 1966 bill recognized the State the authority that could legitimize national cinema by recognizing it as an activity of “marked social interest” and “transcendent public influence” (Roffé, 1996b, p. 216). This would grant filmmakers, critics, film club members, and all those involved in national cinema the status of figures dedicated to a valuable activity of such characteristics.

One problem is that the “social importance” of cinema declared in the bill was not in fact socially recognized. The films that could have aspired to this recognition in the 1960s, before the emergence of the New Venezuelan Cinema, had not had a “transcendent public influence” except as a reason to censor them. One example is what happened with Imagen de Caracas in 1968, a monumental multimedia installation created for the city’s 400th anniversary, of which cinema was the most important component. On the other hand, public significance was not even a reason for a national film to be screened. The best example: Araya, which had shared the National Critics’ Prize (Fipresci) at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival with Hiroshima mon amour by Alain Resnais (France, 1959), only reached Venezuelan cinemas in 1977 when, due to the success of the new national cinema, it was considered potentially profitable to make a Spanish-language version.

Discussions about the Cinema Law resumed the year after the premiere of Cuando quiero llorar no lloro. This must be related to the box office impact of Walerstein’s film, but as a necessary condition, not a sufficient one. The decisive factor was that the New Venezuelan Cinema did indeed succeed with this film in “awakening the interest of the most diverse sectors of the national community” (“Presentación,” 1976). The “marked social interest,” which in the 1966 bill was nothing more than a declaration, became a reality with the “transcendent public influence” that a Venezuelan film achieved for the first time.

It was in this new context that the filmmakers of the New Venezuelan Cinema adhered to the political-cultural strategy when, in 1974, they organized themselves into the National Association of Film Authors (ANAC) to participate in the extra-parliamentary forums where the bill was being debated. The brand-new guild thus began to play the power game independently of the universities, and this had consequences for the legitimacy of filmmakers, although not for this reason.

The shift began by facing a wave of rejection that arose in public opinion. Alfonso Molina (1997) calls it the “great prejudice that was built around national cinema: only films about whores, guerrillas, and thieves” (p. 86). Attributing vast influence to it is contrary to box office successes, but facts such as the ban on Manuel in the city of Maracaibo due to pressure from the Catholic Church and the mobilization of filmmakers in 1977 to ward off attempts to censor three other national films are evidence of its power. This must also be linked to the noted cultural dissent of the New Venezuelan Cinema: it was expanding the narrow boundaries of freedom of expression that were tolerated by democracy.

This is indicative of the fact that filmmakers were beginning to seek legitimacy for national cinema not only as an art form, the practice of which, in turn, should legitimize them as authors, an aspiration expressed in the name of the guild. Nor was it for cultural reasons, but rather as an exercise of democratic freedoms. It was an argument that was added to those put forward in favor of the film law. In his presentation of the statutes of the Film Development Fund, created in 1981, Antonio Llerandi, president of ANAC, mentioned the struggle for freedom of expression as one of the association’s most important struggles (Llerandi, 1983, p. 5).

But the most significant shift in terms of legitimacy was another that also took place in the field of power and must also be linked to the public significance that the New Venezuelan Cinema had acquired. While the 1966 bill proposed allocating the necessary fiscal resources to promote an industry that then existed only on paper, the public success of the New Venezuelan Cinema demonstrated in practice the validity of its “industrial aspirations.” Consequently, just as reality redirected the political-cultural aspect of the strategy towards the defense of freedom of expression, the competitiveness of the new cinema in the national market provided the state with the argument to finance it in line with the policies of the Carlos Andrés Pérez government (1974-1979) for the distribution of the country’s overflowing oil wealth.

The important thing is in what capacity the State recognized the legitimacy of independent filmmakers who still presented themselves as linked to the bipartisan system’s dissident Left, and some of whom had even been guerrilla fighters, such as Luis Correa. Instead of opening up space for them in public cultural institutions, as it had done to reintegrate artists and intellectuals persecuted in the fight against the guerrillas in the 1960s, it undertook the task of supporting their assimilation into the capitalist system as entrepreneurs in an industry that should be promoted with a line of state credit specifically earmarked for cinema.

This was the legitimate social meaning acquired by the expression “author-producers” with which the ANAC filmmakers had identified themselves, regardless of their intentions as artists and defenders of freedom of expression and of the film law; of the thinking expressed in their films about culture, society, and politics; and their rejection of consumerism and the corruption of “Saudi Venezuela.” It led to the consecration in practice of what Roffé (1997b) critically calls “industrialism.” It was not only the current of opinion regarding cinema and cinematographic practices that this author contrasts with the “culturalists” (p. 261). Following Bourdieu once again, industrialism must be considered a habitus of national cinema. It is what has been understood since then, by practical common sense, as the valid way of making films, although the mode of production in universities and experimental cinema in Super 8, for example, was and continued to be different.

Scope and limitations of legitimacy

Finally, it must be considered that the legitimacy to which the New Venezuelan Cinema aspired as a window for freedom of expression and which it achieved as an industry was only possible under the actually existing Venezuelan State. Public opinion is a diffuse legitimizing authority, and the defense of freedom of expression is only guaranteed by the intervention of others, such as the courts. In 1981, for example, as a result of a campaign by filmmakers, Luis Correa was released from prison after being accused of “apology for crime” for his documentary Ledezma, el caso Mamera, (Ledezma, the Mamera Case) but they failed to get the ban on its screening lifted.

The recognition of legitimacy that came with funding was subject, on the other hand, to the “populist system of conciliation” (Rey, 1991), the real way in which the State related to society. It consisted of a network of instances in which the government and interest groups, privileged or not according to the recognition of their share of power, negotiated to resolve conflicts that were also solved through the distribution of public resources.

The priority that conciliation with sectors of greater weight in the system than filmmakers could acquire became evident when the unexpected surplus of income from the oil boom gave way to the economic crisis of 1977-1978. When it became necessary to cut expenses, other interests prevailed over the “legitimate” interests of the national film industry, as Correa’s freedom of expression was overridden because his film affected the interests of the police.

In this new framework, however, exhibitors and distributors also recognized authors and producers as successful entrepreneurs legitimized by state credits. They saw them as capable of providing them with subsidized national products that they could use to replace titles that did not generate profits but were imported to maintain cinema programming. Once the first credits were granted, the filmmakers’ struggle to obtain financing changed. It was no longer a matter of claiming funds for an industry that existed on paper, but of demanding something whose legitimacy had been recognized by the State.

Likewise, as part of the interest it had aroused in all sectors of the country, the private television industry, a historical enemy of the Left, presented itself as a legitimizing force for the New Venezuelan Cinema in the media field. It did so with the founding of the National Academy of Film and Television Arts and Sciences in 1978, the first purchases of films by television channels, and the creation of the El Dorado Awards, an imitation of the Hollywood Oscars.

These awards were presented for the first time in 1980, in a ceremony that was broadcast live by the two private networks and the largest State network. The intention to give them a value analogous to international awards, with the American Academy as a model, was evident. Television’s intention to dispute Venezuelan cinema with the leftist dissidents and assimilate it is also evident when one considers that the awards were presented in the year of the first Venezuelan Film Festival in Mérida, an initiative that had emerged from the academic field.

References

Aguirre, J. M. (1980). “Tendencias actuales en el cine venezolano”, Comunicación, n.° 27, May, pp. 5-14.

—————— (1976). “Hacia un cine industrial venezolano”, Comunicación, n.° 6, February, pp. 35-44.

Anzola, S., Fernández, R. and Messina, F. (1995). “Historia del cineclubismo en Venezuela”, Comunicación, n.° 89, first trimester, pp. 24-35.

Bourdieu, P. (1971 [2002]). “Campo de poder, campo intelectual y hábitus de clase”. In Campo de poder, campo intelectual. Itinerario de un concepto (pp. 97-118). Buenos Aires: Montressor.

Chacón, A. (1970). La izquierda cultural venezolana 1958-1968. Ensayo y antología. Caracas: Domingo Fuentes.

Estadísticas de la industria cinematográfica 1976-1979-1978 (s. f.). Caracas: Ministerio de Fomento, Dirección de Industria Cinematográfica.

González, J., Pino, J. and Vilda, C. (1976). “Vehículo de cultura no. Aquí el cine es negocio”, SIC, n.° 385, pp. 218-221.

Llerandi, A. (1983). “Introducción”. In Por un cine nacional. Acta Constitutiva-Estatutos Sociales del Fondo de Fomento Cinematográfico y Normas para la Comercialización de las Obras Cinematográficas. Caracas: ANAC.

Marrosu, A. (1997). “La empresa perdona un momento de locura”, Cine al Día, n.° 23, April, pp. 29-30.

Molina, A. (2001). Cine, democracia y melodrama. El país de Román Chalbaud. Caracas: Planeta, 2001.

————- (1997). “Cine nacional: 1973-1993. Memoria muy personal del largometraje venezolano”. In Panorama histórico del cine en Venezuela (pp. 75-90). Caracas: Cinemateca Nacional.

Pacheco, C. (1994). “Retrospectiva crítica de Miguel Otero Silva”, Revista Iberoamericana, vol. LX, n.° 166-167, January-June, pp. 185-197.

Paranaguá, P. A. (2003). Tradición y modernidad en el cine de América Latina. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

“Presentación” (1976), Comunicación, n.° 6, February, pp. 2-3.

Rey, J. C. (1991). “La democracia venezolana y la crisis del sistema populista de conciliación”. Revista de Estudios Políticos (nueva época), n.° 74, October-Dicember, pp. 533-578.

Rivas Morente, V. (2012). “El concepto de campo cinematográfico”, Zer, vol. 17, n.° 32, pp. 209-220.

Roffé, A. (1997a). “El nuevo cine venezolano: tendencias, escuelas, géneros”. In Panorama histórico del cine en Venezuela (pp. 51-74).

———– (1997b). “Políticas y espectáculo cinematográfico en Venezuela”. In Panorama histórico del cine en Venezuela (pp. 245-267).