By Omar Vazquez Heredia

Venezuelanvoices: In this article, first published in Nueva Sociedad, Marxist researcher and PSL member, as well as former PCV member, Omar Vazquez Heredia examines the PCV’s efforts to distance itself from the government while still upholding chavismo. He finds that these tensions stem from the growing grievances of the party’s rank-and-file with the State’s handling of the economic crisis and its persecution of labor and social activists, as well as the political calculations of the PCV leadership.

Picture: Telesur, 2018 PCV act in support of Maduro.

The Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV) framed its support for Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro in the terms of its classic strategy of “revolution in two stages”. In its conception, before a “socialist stage”, there had to come one of “national liberation”, requiring an alliance it termed a “broad patriotic national front” with a sector of the “non-monopolistic national bourgeoisie, not associated with and not dependent of imperialist capital”—as reaffirmed in the political lines set by its 14th Congress in 2017.

So, in the conception of the PCV, its support for the Chavista governments would have the objective of supporting the process of national liberation, defining the main enemies as imperialism, represented by the United States, and the “traditional fraction” of the Venezuelan bourgeoisie. In this first stage, the working class would have to accumulate political force and achieve an expansion of its labor and social rights, but without transcending the capital-labor relationship—because the fundamental crux would still be the development of the productive forces to create the material bases that the future transition to socialism would require.

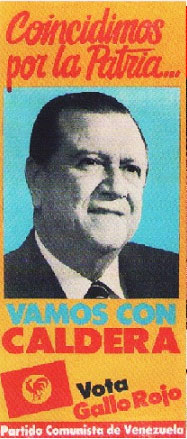

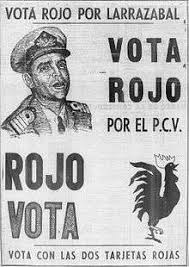

These have been the traditional politics of the PCV throughout its history. Before its alliance with the Chavista movement, these lines led it to support the governments of General Isaias Medina Angarita (1941-1945) and of Vice Admiral Wolfgang Larrazabal (1958), as well as the latter’s presidential candidacy. Also, to the realization of an alliance with nationalists in the military to end the second government of Romulo Betancourt (1959-1964), a close ally of the United States, in the midst of the Cold War. And, finally, to support the candidacy of Rafael Caldera in the 1993 presidential elections, and his presidency during the first two years of his second government (1994-1998).

Venezuelanvoices: PCV posters in support of Caldera in 1993 and Larrazabal in 1958

Maduro and the leadership of the Chavista movement also inherited from Chavez the support of the PCV, amid the calls for unity that proliferated after the last surgery and later death of the historic leader of the Bolivarian Revolution. Thus, in 2013 the PCV urgently convened its 12th National Conference and supported the “son of Chávez” as its presidential candidate. While it endorsed the government program presented by Chavez in 2012 (the so-called Plan de la Patria), it issued circumscribed criticisms of “corruption” and “bureaucracy” in the state apparatus, all within the framework of the so-called “broad anti-imperialist patriotic unity”.

After Maduro’s victory in the presidential elections of April 2013, the PCV put forward economic proposals such as the elimination of the Value Added Tax (VAT), the creation of a state agency to centralize imports, increased taxation of banks, and the suspension of the allocation of foreign currency to the bourgeoisie. Already in 2014, it was recommending a generalized and staggered wage increases. But, in turn, the party made a turn to adapt to the official government discourse about the existence of an “economic war” responsible for high inflation rates and a shortage of goods, which caused a sustained deterioration in real wages. It began to demand “jail for speculators, hoarders and the corrupt”, as agents of “a conspiracy aimed at deepening the weaknesses of the economy [to] reverse the Venezuelan political and social process.”

In reality, the economic recession that began in 2014—along with the steep rise in inflation and shortages of basic products—was caused by the unilateral contraction of foreign currency allocations for imports, as resources were directed to servicing the foreign debt owed by the State and PDVSA, accumulated during the Chavez years. The recession worsened with the collapse of oil prices in 2015, and then after the first US economic sanctions in August 2017.

The application of this inflationary adjustment starting in 2013 kicked off the long and profound process of deterioration in the purchasing power of the wages and pensions, and affected access to basic goods such as food and medicines. However, the concealment or denial of this regressive economic policy allowed the PCV to maintain its alliance with the Maduro government for the parliamentary elections of December 2015, in which the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), the coalition of traditional opposition parties, won two thirds of the National Assembly.

This victory of the MUD, which channeled discontent over the pauperization of living conditions, and the rejection of the government by the majority of the Venezuelan population, was explained by the PCV as a consequence of “not having succeeded in making the masses become aware of the confrontation with imperialism and the oligarchy; that is to say, there would still be a lack of understanding about the sustained and multifaceted imperialist aggression”. Of course, within the framework of this characterization, the PCV defended the Supreme Tribunal of Justice’s rulings against the National Assembly, declaring it in contempt and revoking its powers. This led between 2016 and 2017 to a de facto closure of the Assembly, and the establishment of a dictatorial regime by the Maduro government, legitimized by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ).

Thus, the PCV justified the suspension of democratic rights and cutbacks of civil freedoms, leading to the repression of the massive protests of 2017. These began in defense of the National Assembly, and later became an expression of all popular discontent, with widespread peaceful demonstrations and some violent events. In the PCV’s perspective, “the reactionary violent offensive could be neutralized and defeated with effective, coherent and forceful action by the institutions and the people.” Of course, the PCV conceived of this protest movement as one by the “fascist right,” to be confronted. For this reason, it also supported the imposition without consultation of the Constituent Assembly in August 2017, although rhetorically requesting that it be “revolutionary.”

But the sharp decline in real wages, and the blatant profiteering around foreign currency allocation by high officials and crony businessmen, generated pressures on the PCV that contradicted its political support for the Government. In 2017—setting the programmatic basis for the current rupture of the alliance with Maduro—the political lines of the Party changed. The 15th Party Congress found that “the conflicts in the Bolivarian bloc are sharpening, as a part of it has changed its class condition to become part of the different sectors of the bourgeoisie, producing non-antagonistic inter-capitalist contradictions.” It also highlighted the need to organize a “popular revolutionary bloc”—the germ of today’s Popular Revolutionary Alternative (APR).

These programmatic changes did not translate into an immediate break with the government. On the contrary, the PCV supported Maduro in the questioned presidential elections of May 2018, because, in its opinion, the aggressiveness of the escalation of US imperialism and its European allies put the prospect of national liberation at risk. To try to protect itself from pressure from its own bases and some of its leaders, the PCV leadership signed a programmatic agreement with Maduro at its headquarters, which proposed “prioritizing formal employment with rights” and “strengthening wages and restoring them as the primary and main component of income.”

Going against to what he signed with the PCV, in July and August 2018, the Maduro government began the application of the so-called “Economic Recovery, Growth and Prosperity Program” that included a mega-devaluation of the official currency exchange rate, the elimination of price controls, the exoneration of tariffs for importing entrepreneurs, and the elimination of income taxes for PDVSA and its transnational capital partners in joint ventures. This was followed by the regressive labor reform under the Memorandum 2792, issued on October 11 of 2018 by Minister of Labor Eduardo Piñate.

The execution of Memorandum 2792 has been central in the process of distancing the PCV from the government, since it promotes the destruction of working class wages, and regressive changes in labor relations. 2792 set up a governmental ‘technical’ committee to adapt and fit collective labor contracts to government-set wage scales—effectively ending collective bargaining for workers over labor contracts, violating the principle of progressivity of wage increases, and affecting the concept of ‘wages’ itself—sponsored massive and indirect lay-offs in private companies through the mechanism of suspension of workers with the continued payment of a worthless minimum wage without compensatory bonuses, and, by suppressing the complaints offices of the Labor Inspectorates, eliminated the right to strike.

The result sought, and achieved, by maintaining a devalued minimum wage in Bolivars and establishing food vouchers anchored in foreign currency, was the voucherization of most of the wage income of the working class. This also impacted and reduced other benefits, calculated according to salary, such as paid time off and vacations, employee’s statutory profit sharing, social benefits, and overtime and night-work pay. Capitalists have been applying this voucherization of the wage since 2018, with payment in vouchers of between $30 and $50 monthly, with the objective of avoiding the massive desertion of the workforce, part of which has migrated or turned to informal commerce. Now, in 2021, Maduro’s government has formalized this labor policy, starting with an imposed collective contract for oil workers that establishes a monthly pay of Bs.S. 137 million ($74.11), mostly composed of transportation and food vouchers, as the wage component amounts to only Bs.S. 5 million ($2.70). (Translator’s note: since the publishing of the article, devaluation has further diminished these figures in dollars).

Responses by trade unions to Memorandum 2792 began in 2018 itself, and were significant, with the constitution and protests of the Intersector Workers of Venezuela (ITV) in November of that year. The ITV saw the confluence of important union leaders from different economic branches, and members of political organizations of critical Chavismo, the traditional opposition and the independent left. The PCV did not participate in the ITV, but political and union sectors allied with its labor front did. This increased the pressure from the rank-and-file and some party leaders for the Party to distance itself from the government. Although the Party conceived the ITV as led by “oppositionist” and “a certain anti-Chavista left”, it also recognized the “participation of worker leaders with revolutionary militancy.”

Another factor influencing the PCV’s break with the government lays in the field of agrarian relations, with the application of a State policy to evict peasants and hand over land to old and new landowners. In July of 2018, the PCV participated in the “Admirable Peasant March” to Caracas, received by Maduro under pressure of militant Chavista sectors. However, the evictions and governmental neglect towards peasant producers continued, in the context of the government’s alliance with large and medium-sized agricultural enterprises sponsored by Wilmar Castro Soteldo, the Minister of Agriculture and Land, who dubs them “a revolutionary bourgeoisie”. In this climate of conflict in the countryside, October 2018 saw the murder of peasant leader and PCV Central Committe member Luis Fajardo, a crime which remains unpunished.

In the course of 2019, and until the creation of the APR in August 2020, the PCV carried out a contradictory and opportunistic policy of complaints and protests against high-ranking officials such as ministers Piñate and Castro Soteldo, but without questioning the main agent responsible for the labor and agrarian policies it critiqued: the Venezuelan president. At the same time, it also supported the government’s corrupt maneuvers to dismantle Juan Guaido’s attempted parallel government—allied with the United States and defender of reprehensible economic sanctions that aggravate the impoverishment of the popular classes, while creating opportunities for corruption among the traditional opposition. In January 2020, after the Scorpion Operation, the PCV returned to the National Assembly and backed Luis Parra, whom the Maduro government imposed as president of the Assembly in alliance with a group of deputies it had bribed to split the Opposition bloc.

Venezuelanvoices: “With the strength of Chavez” was one of the slogans used by APR in the 2020 electoral campaign in an effort to claim representation of true chavismo.

Venezuelanvoices: “With the strength of Chavez” was one of the slogans used by APR in the 2020 electoral campaign in an effort to claim representation of true chavismo.

The PCV’s isolated complaints and protests at the headquarters of the Ministry of Labor and the National Land Institute, and its requests for government rectification, did not reverse the application state policies that benefited business sectors and accentuated de destruction of real wages. On the contrary, between 2018 and 2020, Maduro’s response was to double down on criminalizing labor protests and dissent in the oil industry, the primary metal industries in Guayana, the public administration and the health and education sectors—the latter convoking national strikes of nurses in 2018 and of teachers in 2019. Several labor leaders, such as Deillily Rodríguez and Jairo Colmenarez from the Caracas Metro, William Prieto from FOGADE and PDVSA’s Jose Bodas were fired or forced into retirement. Carupano teacher Robert Franco, Ruben Gonzalez and Tania Rodriguez from Ferrominera, Elio Mendoza from SIDOR, and from PDVSA, Marcos Sabariego, Gil Mujica, Bartolo Guerra, Darío Salcedo, Eudis Girot, and Guillermo Zarraga, are among the multitude of trade union leaders from state-owned enterprises that have been arrested, and remain under house arrest or imprisoned in military cells.

In this context, under pressure from its bases and some leaders, and trying to channel the discontent of grassroots sectors of Chavismo, along with other Chavista political parties and organizations, the PCV constituted the Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APR) in August of 2020, to participate in the questioned and boycotted December 2020 parliamentary elections. Maduro’s response was equally authoritarian: the Supreme Tribunal of Justice intervened the Chavista APR member parties Homeland for All (PPT) and Tupamaros, and delivered them to pro-government leaderships. APR candidates were harassed, dismissed from their jobs or arrested, in a campaign against what Maduro termed the “sleep deprived Left”. (Translator’s note: the term “izquierda trasnochada”, presumably coined by Romulo Betancourt, who ruled Venezuela in the 1960’s, has historically been used by socialdemocrats and right wingers in to cartoonishly portray the Left as outdated, out of touch with reality).

Maduro’s attacks against the izquierda trasnochada were meant to counter the critiques by the APR and left opposition groups of the so-called “Anti-Blockade Law” passed by the imposed National Constituent Assembly. This law proposes in its articles 26 and 29 a deepening of the government’s privatization policies. After the 2021 parliamentary elections—which were widely boycotted—the newly-elected, Maduro-controlled National Assembly began to hold meetings with business associations such as Fedecamaras (chambers of commerce) and Conindustria (private industries), to open negotiations on the division of spoils over the privatization of state companies and assets, in exchange for support in requesting the lifting of foreign economic and individual sanctions, in an attempt to opening a public negotiation with the Biden administration and the European Union. Meanwhile the government continued its attacks on the PCV, accusing it of serving imperialist interests, and cutting the speaking rights of the sole PCV member in the National Assembly, Oscar Figuera.

On January 30 of 2021, the PCV responded with a statement, that without saying it expressly, constitutes a break with Maduro. In it, the Party denounced the implementation underway of a “brutal neoliberal adjustment” and urged “to correct this call to intolerance, hatred, persecution and disrespect for the exercise of political and democratic rights.”

Yet those policies that the PCV now totally rejects have their origin in the inflationary adjustment that began in 2013 and in the attempts to attract transnational capital with the 2014 decree-law of foreign investment and Special Economic Zones and the opening up of the Orinoco Mining Arc—and the consolidation since 2016 of a dictatorial regime. Only now the PCV recognizes the authoritarian policies of the Maduro Government, warning in the above-mentioned document that this path “may lead to fascism.”

However, although it is an advance for the PCV to recognize this, the Party still limits itself to defending the democratic rights and freedoms for Chavista militants only, as if it be right that the rest of the Venezuelan population of different political orientations should be deprived of political rights. In this, they remain in agreement with the leaders of the Chavista government.

The “critical Chavismo” of the PCV that opposes Maduro—while still vindicating Chavez and his contributions to the so-called national liberation—has already failed before, when it was pursued by Marea Socialista and Redes. Chavismo is a national-populist movement with military characteristics, with a logic of command-obedience between leadership and bases. PCV can only channel the grievances of militant Chavistas, yielding it derisory results in the 2021 parliamentary elections.

Thank you! Glad you like it.

LikeLike